Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

Literary devices are perhaps the greatest tools that writers have in literature. Just think — Shakespeare could have written: Everyone has a role in life.

Instead, he used a literary device and penned what is likely the most famous metaphor in literature:

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women merely players

And the rest is history.

A literary device is a writing technique that writers use to express ideas, convey meaning, and highlight important themes in a piece of text. A metaphor, like we mentioned earlier, is a famous example of a literary device.

These devices serve a wide range of purposes in literature. Some might work on an intellectual level, while others have a more emotional effect. They may also work subtly to improve the flow of your writing. No matter what, if you're looking to inject something special into your prose, literary devices are a great place to start.

A writer using a literary device is quite different from a reader identifying it. Often, an author’s use of a literary device is subtle by design —you only feel its effect, and not its presence.

Therefore, we’ve structured this post for both purposes:

Alliteration describes a series of words in quick succession that all start with the same letter or sound. It lends a pleasing cadence to prose and Hamlet and the dollar as currency in Macbeth.

Example: “One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die.” — “Death, Be Not Proud” by John Donne

Exercise: Pick a letter and write a sentence where every word starts with that letter or one that sounds similar.

Anaphora is the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of a series of clauses or sentences. It’s often seen in poetry and speeches, intended to provoke an emotional response in its audience.

Example: Martin Luther King’s 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech.

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.

"… and I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit together at the table of brotherhood.

"… I have a dream that little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

Exercise: Pick a famous phrase and write a paragraph elaborating on an idea, beginning each sentence with that phrase.

Related term: repetition

Anastrophe is a figure of speech wherein the traditional sentence structure is reversed. So a typical verb-subject-adjective sentence such as “Are you ready?” becomes a Yoda-esque adjective-verb-subject question: “Ready, are you?” Or a standard adjective-noun pairing like “tall mountain” becomes “mountain tall.”

Example: “Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing.” — “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

Exercise: Write a standard verb-subject-adjective sentence or adjective-noun pairing then flip the order to create an anastrophe. How does it change the meaning or feeling of the sentence?

Chiasmus is when two or more parallel clauses are inverted. “Why would I do that?” you may be wondering. Well, a chiasmus might sound confusing and unnecessary in theory, but it's much more convincing in practice — and in fact, you've likely already come across it before.

Example: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” — John F. Kennedy

Congeries is a fancy literary term for creating a list. The items in your list can be words, ideas, or phrases, and by displaying them this way helps prove or emphasize a point — or even create a sense of irony. Occasionally, it’s also called piling as the words are “piling up.”

Example: "Apart from better sanitation and medicine and education and irrigation and public health and roads and a freshwater system and baths and public order, what have the Romans done for us?" — Monty Python’s Life of Brian

A cumulative sentence (or “loose sentence”) is one that starts with an independent clause, but then has additional or modifying clauses. They’re often used for contextual or clarifying details. This may sound complex, but even, “I ran to the store to buy milk, bread, and toilet paper” is a cumulative sentence, because the first clause, “I ran to the store,” is a complete sentence, while the rest tells us extra information about your run to the store.

Example: “It was a large bottle of gin Albert Cousins had brought to the party, yes, but it was in no way large enough to fill all the cups, and in certain cases to fill them many times over, for the more than one hundred guests, some of whom were dancing not four feet in front of him.” – Commonwealth by Ann Patchett

Example: Write three sentences that are related to each other. Can you combine the information into a cumulative sentence?

Literary Devices Cheatsheet

Master these 40+ devices to level up your writing skills.

Epistrophe is the opposite of anaphora, with this time a word or phrase being repeated at the end of a sentence. Though its placement in a sentence is different it serves the same purpose—creating emphasis—as an anaphora does.

Example: “I’ll be ever’where – wherever you look. Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. If Casy knowed, why, I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad an’ – I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry an’ they know supper’s ready. An’ when our folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build, why, I’ll be there.” — The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Related terms: repetition, anaphora

Exercise: Write a paragraph where a phrase or a word is repeated at the end of every sentence, emphasizing the point you’re trying to make.

Erotesis is a close cousin of the rhetorical question. Rather than a question asked without expectation of an answer, this is when the question (and the asker) confidently expects a response that is either negative or affirmative.

Example: “Do you then really think that you have committed your follies in order to spare your son them?” — Siddhartha by Herman Hesse

Related term: rhetorical question

Hyperbaton is the inversion of words, phrases, or clauses in a sentence that differs from how they would normally be arranged. It comes from the Greek hyperbatos, which means “transposed” or “inverted.” While it is similar to anastrophe, it doesn’t have the same specific structure and allows you to rearrange your sentences in whatever order you want.

Example: “Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire.” — “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe

Related terms: anastrophe, epistrophe

If you’re a neat freak who likes things just so, isocolon is the literary device for you. This is when two or more phrases or clauses have similar structure, rhythm, and even length — such that, when stacked up on top of each other, they would line up perfectly. Isocolon often crops up in brand slogans and famous sayings; the quick, balanced rhythm makes the phrase catchier and more memorable.

Example: Veni, vidi, vici (“I came, I saw, I conquered”)

Litotes (pronounced lie-toe-teez) is the signature literary device of the double negative. Writers use litotes to express certain sentiments through their opposites, by saying that that opposite is not the case. Don’t worry, it makes more sense with the examples. 😉

Examples: “You won’t be sorry” (meaning you’ll be happy); “you’re not wrong” (meaning you’re right); “I didn’t not like it” (meaning I did)

If Shakespeare is the king of metaphors, Michael Scott is the king of malapropisms. A malapropism is when similar-sounding words replace their appropriate counterparts, typically to comic effect — one of the most commonly cited is “dance a flamingo,” rather than a “flamenco.” Malapropisms are often employed in dialogue when a character flubs up their speech.

Example: “I am not to be truffled with.”

Exercise: Choose a famous or common phrase and see if you can replace a word with a similar sounding one that changes the meaning.

Amusingly, onomatopoeia (itself a difficult-to-pronounce word) refers to words that sound like the thing they’re referring to. Well-known instances of onomatopoeia include whiz, buzz, snap, grunt, etc.

Example: The excellent children's book Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type. “Farmer Brown has a problem. His cows like to type. All day long he hears: Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. Clickety, clack, moo.”

Exercise: Take some time to listen to the sounds around you and write down what you hear. Now try to use those sounds in a short paragraph or story.

An oxymoron comes from two contradictory words that describe one thing. While juxtaposition contrasts two story elements, oxymorons are about the actual words you are using.

Example: "Parting is such sweet sorrow.” — Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. (Find 100 more examples of oxymorons here.)

Related terms: juxtaposition, paradox

Exercise: Choose two words with opposite meanings and see if you can use them in a sentence to create a coherent oxymoron.

Parallelism is all about your sentence structure. It’s when similar ideas, sounds, phrases, or words are arranged in a way that is harmonious or creates a parallel, hence the name. It can add rhythm and meter to any piece of writing and can often be found in poetry.

Example: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” — Neil Armstrong

Find out which literary luminary is your stylistic soulmate. Takes one minute!

Instead of using a single conjunction in lengthy statements, polysyndeton uses several in succession for a dramatic effect. This one is definitely for authors looking to add a bit of artistic flair to their writing, or who are hoping to portray a particular (usually naïve) sort of voice.

Example: “Luster came away from the flower tree and we went along the fence and they stopped and we stopped and I looked through the fence while Luster was hunting in the grass.” — The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

Exercise: Write three or four independent sentences. Try combining them using conjunctions. What kind of effect does this have on the overall meaning and tone of the piece?

A portmanteau is when two words are combined to form a new word which refers to a single concept that retains the meanings of both the original words. Modern language is full of portmanteaus. In fact, the portmanteau is itself a portmanteau. It’s a combination of the French porter (to carry) and manteau (cloak).

Example: Brunch (breakfast and lunch); cosplay (costume and roleplay); listicle (list and article); romcom (romance and comedy)

Exercise: Pick two words that are often used together to describe a single concept. See if there’s a way to combine them and create a single word that encompasses the meaning of both.

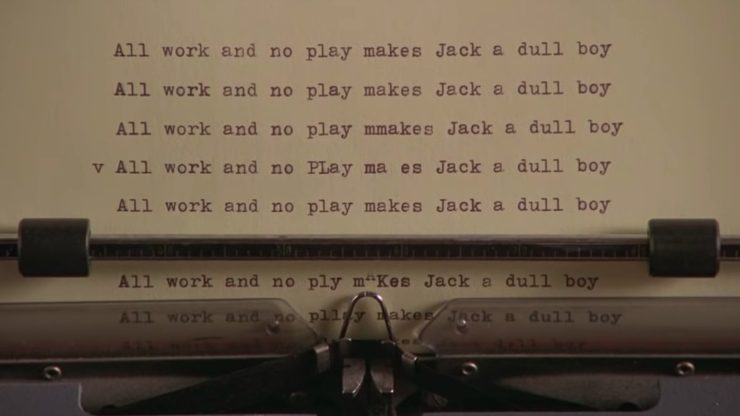

Repetition, repetition, repetition… where would we be without it? Though too much repetition is rarely a good thing, occasional repetition can be used quite effectively to drill home a point, or to create a certain atmosphere. For example, horror writers often use repetition to make the reader feel trapped and scared.

Example: In The Shining, Jack Torrance types over and over again on his pages, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” In this case, obsessive repetition demonstrates the character’s unraveling mind.

Related term: anaphora

Exercise: Repetition can be used to call attention to an idea or phrase. Pick an idea you want to emphasize and write a few sentences about it. Are there any places where you can add repetition to make it more impactful?

A tautology is when a sentence or short paragraph repeats a word or phrase, expressing the same idea twice. Often, this is a sign that you should trim your work to remove the redundancy (such as “frozen ice”) but can also be used for poetic emphasis.

Example: "But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping, And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door" – “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

Tmesis is when a word or phrase is broken up by an interjecting word, such as abso-freaking-lutely. It’s used to draw out and emphasize the idea, often with a humorous or sarcastic slant.

Example: "This is not Romeo, he's some-other-where." – Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

An allegory is a type of narrative that uses characters and plot to depict abstract ideas and themes. In an allegorical story, things represent more than they appear to on the surface. Many children's fables, such as The Tortoise and the Hare, are simple allegories about morality — but allegories can also be dark, complex, and controversial.

Example: Animal Farm by George Orwell. This dystopian novella is one of modern literature’s best-known allegories. A commentary on the events leading up to Stalin's rise and the formation of the Soviet Union, the pigs at the heart of the novel represent figures such as Stalin, Trotsky, and Molotov.

Exercise: Pick a major trend or problem in the world and consider what defines it. Try and create a story where that trend plays out on a smaller scale.

For more inspiration for how to use allegories to explore your themes, check out this guide on themes.

An anecdote is like a short story within a story. Sometimes, they are incredibly short—only a line or two—and their purpose is to add a character’s perspective, knowledge, or experience to a situation. They can be inspirational, humorous, or be used to inspire actions in others. Since anecdotes are so short, don’t expect them to be part of a main story. They’re usually told by a character and part of the dialogue.

Example: Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way, part of his series of novels, In Search of Lost Time, deals with the themes of remembrance and memory. In one section of this book, to illustrate these ideas, the main character recalls an important memory of eating a madeleine cookie. “Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, save what was comprised in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent out for one of those short, plump little cakes called ‘petites madeleines,’ which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted scallop of a pilgrim’s shell.”

Literally meaning “god in the machine” in Greek, deus ex machina is a plot device where an impossible situation is solved by the appearance of an unexpected or unheard of character, action, object, or event. This brings about a quick and usually happy resolution for a story and can be used to surprise an audience, provide comic relief, or provide a fix for a complicated plot. However, deus ex machinas aren’t always looked upon favorably and can sometimes be seen as lazy writing, so they should be used sparingly and with great thought.

Example: William Golding’s famous novel of a group of British boys marooned on a desert island is resolved with a deus ex machina. At the climax of The Lord of the Flies, as all threads converge and Ralph is about to be killed by Jack, a naval officer arrives to rescue the boys and bring them back to civilization. It’s an altogether unexpected and bloodless ending for a story about the boys’ descent into savagery.

Exercise: Consider the ending of your favorite book or movie and then write an alternate ending that uses a deus ex machina to resolve the main conflict. How does this affect the overall story in terms of theme and tone?

If you struggle to write consistently, sign up for our How to Write a Novel course to finish a novel in just 3 months.

NEW REEDSY COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

Dramatic irony is when the readers know more about the situation going on than at least one of the characters involved. This creates a difference between the ways the audience and the characters perceive unfolding events. For instance, if we know that one character is having an affair, when that character speaks to their spouse, we will pick up on the lies and double-meanings of their words, while the spouse may take them at face value.

Example: In Titanic, the audience knows from the beginning of the movie that the boat will sink. This creates wry humor when characters remark on the safety of the ship.

Exposition is when the narrative provides background information in order to help the reader understand what’s going on. When used in conjunction with description and dialogue, this literary device provides a richer understanding of the characters, setting, and events. Be careful, though — too much exposition will quickly become boring, thus undercutting the emotional impact of your work.

Example: “The Dursley’s had everything they wanted, but they also had a secret, and their greatest fear was that somebody would discover it.” – Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling

Exercise: Pick your favorite story and write a short paragraph introducing it to someone who knows nothing about it.

Flashbacks to previous events split up present-day scenes in a story, usually to build suspense toward a big reveal. Flashbacks are also an interesting way to present exposition for your story, gradually revealing to the reader what happened in the past.

Example: Every other chapter in the first part of Gone Girl is a flashback, with Amy’s old diary entries describing her relationship with her husband before she disappeared.

Related term: foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is when the author hints at events yet to come in a story. Similar to flashbacks (and often used in conjunction with them), this technique is also used to create tension or suspense — giving readers just enough breadcrumbs to keep them hungry for more.

Example: One popular method of foreshadowing is through partial reveals — the narrator leaves out key facts to prompt readers’ curiosity. Jeffrey Eugenides does this in The Virgin Suicides: “On the morning the last Lisbon daughter took her turn at suicide — it was Mary this time, and sleeping pills, like Therese, the two paramedics arrived at the house knowing exactly where the knife drawer was, and the gas oven, and the beam in the basement from which it was possible to tie a rope.”

Related term: flashback

Exercise: Go back to your favorite book or movie. Can you identify any instances of foreshadowing in the early portions of the story for events that happen in the future?

A frame story is any part of the story that "frames" another part of it, such as one character telling another about their past, or someone uncovering a diary or a series of news articles that then tell the readers what happened. Since the frame story supports the rest of the plot, it is mainly used at the beginning and the end of the narrative, or in small interludes between chapters or short stories.

Example: In The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss, Kvothe is telling Chronicler the story of his life over the span of three days. Most of the novel is the story he is telling, while the frame is any part that takes place in the inn.

In medias res is a Latin term that means "in the midst of things" and is a way of starting a narrative without exposition or contextual information. It launches straight into a scene or action that is already unfolding.

Example: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” — The opening line of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

Exercise: Pick a story you enjoy and rewrite the opening scene so that it starts in the middle of the story.

Point of view is, of course, the mode of narration in a story. There are many POVs an author can choose, and each one will have a different impact on the reading experience.

Example: Second person POV is uncommon because it directly addresses the reader — not an easy narrative style to pull off. One popular novel that manages to employ this perspective successfully is Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney: “You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning. But here you are, and you cannot say that the terrain is entirely unfamiliar, although the details are fuzzy.”

Exercise: Write a short passage in either first, second, or third person. Then rewrite that passage in the other two points of view, only changing the pronouns. How does the change in POV affect the tone and feel of the story?

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

Soliloquy involves a character speaking their thoughts aloud, usually at length (and often in a Shakespeare play). The character in question may be alone or in the company of others, but they’re not speaking for the benefit of other people; the purpose of a soliloquy is for a character to reflect independently.

Example: Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” speech, in which he ruminates on the nature of life and death, is a classic dramatic soliloquy.

Exercise: Pick a character from your favorite book or movie and write a soliloquy from their point of view where they consider their thoughts and feelings on an important part of their story or character arc.

Find out here! Takes 30 seconds

Tone refers to the overall mood and message of your book. It’s established through a variety of means, including voice, characterization, symbolism, and themes. Tone sets the feelings you want your readers to take away from the story.

Example: No matter how serious things get in The Good Place, there is always a chance for a character to redeem themselves by improving their behavior. The tone remains hopeful for the future of humanity in the face of overwhelming odds.

Exercise: Write a short paragraph in an upbeat tone. Now using the same situation you came up with, rewrite that passage in a darker or sadder tone.

Tragicomedy is just what it sounds like: a blend of tragedy and comedy. Tragicomedy helps an audience process darker themes by allowing them to laugh at the situation even when circumstances are bleak.

Example: Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events uses wordplay, absurd situations, and over-the-top characters to provide humor in an otherwise tragic story.

An allusion is a reference to a person, place, thing, concept, or other literary work that a reader is likely to recognize. A lot of meaning can be packed into an allusion and it’s often used to add depth to a story. Many works of classic Western literature will use allusions to the Bible to expand on or criticize the morals of their time.

Example: “The two knitting women increase his anxiety by gazing at him and all the other sailors with knowing unconcern. Their eerie looks suggest that they know what will happen (the men dying), yet don’t care.” The two women knitting in this passage from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness are a reference to the Fates from Greek mythology, who decide the fate of humanity by spinning and cutting the threads of life.

Exercise: In a relatively simple piece of writing, see how many times you can use allusions. Go completely crazy. Once you’re finished, try to cut it down to a more reasonable amount and watch for how it creates deeper meaning in your piece.

An analogy connects two seemingly unrelated concepts to show their similarities and expand on a thought or idea. They are similar to metaphors and similes, but usually take the comparison much further than either of these literary devices as they are used to support a claim rather than provide imagery.

Example: “It has been well said that an author who expects results from a first novel is in a position similar to that of a man who drops a rose petal down the Grand Canyon of Arizona and listens for the echo.” — P.G. Wodehouse

Exercise: Pick two seemingly unrelated nouns and try to connect them with a verb to create an analogy.

To anthropomorphize is to apply human traits or qualities to a non-human thing such as objects, animals, or the weather. But unlike personification, in which this is done through figurative description, anthropomorphism is literal: a sun with a smiling face, for example, or talking dogs in a cartoon.

Examples: In Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, Mrs. Potts the teapot, Cogsworth the clock, and Lumière the candlestick are all household objects that act and behave like humans (which, of course, they were when they weren’t under a spell).

Related term: personification

Exercise: Pick a non-human object and describe it as if it was human, literally ascribing human thoughts, feelings, and senses to it.

An aphorism is a universally accepted truth stated in a concise, to-the-point way. Aphorisms are typically witty and memorable, often becoming adages or proverbs as people repeat them over and over.

Example: “To err is human, to forgive divine.” — Alexander Pope

An archetype is a “universal symbol” that brings familiarity and context to a story. It can be a character, a setting, a theme, or an action. Archetypes represent feelings and situations that are shared across cultures and time periods, and are therefore instantly recognizable to any audience — for instance, the innocent child character, or the theme of the inevitability of death.

Example: Superman is a heroic archetype: noble, self-sacrificing, and drawn to righting injustice whenever he sees it.

Exercise: Pick an archetype — either a character or a theme — and use it to write a short piece centered around that idea.

To learn more about archetypes, check out these 12 common ones that all writers should know.

A cliché is a saying or idea that is used so often it becomes seen as unoriginal. These phrases might become so universal that, despite their once intriguing nature, they're now looked down upon as uninteresting and overused.

Examples: Some common cliches you might have encountered are phrases like “easy as pie” and “light as a feather.” Some lines from famous books and movies have become so popular that they are now in and of themselves cliches such as Darth Vader’s stunning revelation from The Empire Strikes Back, “Luke, I am your father.” Also, many classic lines of Shakespeare are now considered cliches like, “All that glitters is not gold” from The Merchant of Venice.

Exercise: Write a short passage using as many cliches as possible. Now try to cut them out and replace them with more original phrasing. See how the two passages compare.

Colloquialism is the use of casual and informal language in writing, which can also include slang. Writers use colloquialisms to provide context to settings and characters, and to make their writing sound more authentic, especially in spoken form. Imagine reading a YA novel that takes place in modern America, and the characters speak to each other like this:

“Good morning, Sue. I hope that you slept well and are prepared for this morning’s science exam.”

It’s not realistic. Colloquialisms help create believable dialogue:

“Hey Sue, what’d you get up to last night? This science test is gonna suck.”

Example: Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh takes place in Scotland, a fact made undeniably obvious by the dialect: “Thing is, as ye git aulder, this character-deficiency gig becomes mair sapping. Thir wis a time ah used tae say tae aw the teachers, bosses, dole punters, poll-tax guys, magistrates, when they telt me ah was deficient: ’Hi, cool it, gadge, ah’m jist me, jist intae a different sort ay gig fae youse but, ken?’”

Exercise: Write a dialogue between two characters as formally as possible. Now take that conversation and make it more colloquial. Imagine that you’re having this conversation with a friend. Mimic your own speech patterns as you write.

A euphemism is an indirect, “polite” way of describing something too inappropriate or awkward to address directly. However, most people will still understand the truth about what's happening.

Example: When an elderly person is forced to retire, some might say they’re being “put out to pasture.”

Exercise: Write a paragraph where you say things very directly. Now rewrite that paragraph using only euphemisms.

Hyperbole is an exaggerated statement that emphasizes the significance of the statement’s actual meaning. When a friend says, "Oh my god, I haven't seen you in a million years," that's hyperbole.

Example: “At that time Bogotá was a remote, lugubrious city where an insomniac rain had been falling since the beginning of the 16th century.” — Living to Tell the Tale by Gabriel García Márquez

Exercise: Tall tales often make use of hyperbole to tell an exaggerated story. Use hyperbole to relate a completely mundane event or experience to turn it into a tall tale.

Hypophora is much like a rhetorical question, wherein someone asks a question that doesn't require an answer. However, in hypophora, the person raises a question and answers it immediately themselves (hence the prefix hypo, meaning 'under' or 'before'). It’s often used when characters are reasoning something aloud.

Example: “Do you always watch for the longest day of the year and then miss it? I always watch for the longest day in the year and then miss it.” — Daisy in The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

An idiom is a saying that uses figurative language whose meaning differs from what it literally says. These phrases originate from common cultural experiences, even if that experience has long ago been forgotten. Without cultural context, idioms don’t often make sense and can be the toughest part for non-native speakers to understand.

Example: In everyday use, idioms are fairly common. We say things like, “It’s raining cats and dogs” to say that it’s downpouring.

Exercise: Idioms are often used in dialogue. Write a conversation between two people where idioms are used to express their main points.

Imagery appeals to readers’ senses through highly descriptive language. It’s crucial for any writer hoping to follow the rule of "show, don’t tell," as strong imagery truly paints a picture of the scene at hand.

Example: “In the hard-packed dirt of the midway, after the glaring lights are out and the people have gone to bed, you will find a veritable treasure of popcorn fragments, frozen custard dribblings, candied apples abandoned by tired children, sugar fluff crystals, salted almonds, popsicles, partially gnawed ice cream cones and wooden sticks of lollipops.” — Charlotte's Web by E.B. White

Exercise: Choose an object, image, or idea and use the five senses to describe it.

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

Irony creates a contrast between how things seem and how they really are. There are three types of literary irony: dramatic (when readers know what will happen before characters do), situational (when readers expect a certain outcome, only to be surprised by a turn of events), and verbal (when the intended meaning of a statement is the opposite of what was said).

Example: This opening scene from Orson Welles’ A Touch of Evil is a great example of how dramatic irony can create tension.

Juxtaposition places two or more dissimilar characters, themes, concepts, etc. side by side, and the profound contrast highlights their differences. Why is juxtaposition such an effective literary device? Well, because sometimes the best way for us to understand something is by understanding what it’s not.

Example: In the opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens uses juxtaposition to emphasize the societal disparity that led to the French Revolution: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness…”

Related terms: oxymoron, paradox

Exercise: Pick two ideas, objects, places, or people that seem like complete opposites. Introduce them side by side in the beginning of your piece and highlight their similarities and differences throughout.

A metaphor compares two similar things by saying that one of them is the other. As you'd likely expect, when it comes to literary devices, this one is a heavy hitter. And if a standard metaphor doesn't do the trick, a writer can always try an extended metaphor: a metaphor that expands on the initial comparison through more elaborate parallels.

Example: Metaphors are literature’s bread and butter (metaphor intended) — good luck finding a novel that is free of them. Here’s one from Frances Hardinge’s A Face Like Glass: “Wishes are thorns, he told himself sharply. They do us no good, just stick into our skin and hurt us.”

Related term: simile

Exercise: Write two lists: one with tangible objects and the other concepts. Mixing and matching, try to create metaphors where you describe the concepts using physical objects.

Metonymy is like symbolism, but even more so. A metonym doesn’t just symbolize something else, it comes to serve as a synonym for that thing or things — typically, a single object embodies an entire institution.

Examples: “The crown” representing the monarchy, “Washington” representing the U.S. government.

Related term: synecdoche

Exercise: Create a list of ten common metonymies you might encounter in everyday life and speech.

Whatever form a motif takes, it recurs throughout the novel and helps develop the theme of the narrative. This might be a symbol, concept, or image.

Example: In Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy, trains are an omnipresent motif that symbolize transition, derailment, and ultimately violent death and destruction.

Related term: symbol

Exercise: Pick a famous book or movie and see if you can identify any common motifs within it.

Non sequiturs are statements that don't logically follow what precedes them. They’ll often be quite absurd and can lend humor to a story. But they’re just not good for making jokes. They can highlight missing information or a miscommunication between characters and even be used for dramatic effect.

Example: “It was a spring day, the sort that gives people hope: all soft winds and delicate smells of warm earth. Suicide weather.” — Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen

Exercise: Write a conversation that gets entirely derailed by seemingly unrelated non sequiturs.

Paradox derives from the Greek word paradoxon, which means “beyond belief.” It’s a statement that asks people to think outside the box by providing seemingly illogical — and yet actually true — premises.

Example: In George Orwell’s 1984, the slogan of the totalitarian government is built on paradoxes: “War is Peace, Freedom is Slavery, Ignorance is Strength.” While we might read these statements as obviously contradictory, in the context of Orwell’s novel, these blatantly corrupt sentiments have become an accepted truth.

Related terms: oxymoron, juxtaposition

Exercise: Try writing your own paradox. First, think of two opposing ideas that can be juxtaposed against each other. Then, create a situation where these contradictions coexist with each other. What can you gather from this unique perspective?

Personification uses human traits to describe non-human things. Again, while the aforementioned anthropomorphism actually applies these traits to non-human things, personification means the behavior of the thing does not actually change. It's personhood in figurative language only.

Example: “Just before it was dark, as they passed a great island of Sargasso weed that heaved and swung in the light sea as though the ocean were making love with something under a yellow blanket, his small line was taken by a dolphin.” — The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

Related term: anthropomorphism

Exercise: Pick a non-human object and describe it using human traits, this time using similes and metaphors rather than directly ascribing human traits to it.

A rhetorical question is asked to create an effect rather than to solicit an answer from the listener or reader. Often it has an obvious answer and the point of asking is to create emphasis. It’s a great way to get an audience to consider the topic at hand and make a statement.

Example: “If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?” — The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare

Writers use satire to make fun of some aspect of human nature or society — usually through exaggeration, ridicule, or irony. There are countless ways to satirize something; most of the time, you know it when you read it.

Example: The famous adventure novel Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift is a classic example of satire, poking fun at “travelers' tales,” the government, and indeed human nature itself.

A simile draws resemblance between two things by saying “Thing A is like Thing B,” or “Thing A is as [adjective] as Thing B.” Unlike a metaphor, a similar does not posit that these things are the same, only that they are alike. As a result, it is probably the most common literary device in writing — you can almost always recognize a simile through the use of “like” or “as.”

Example: There are two similes in this description from Circe by Madeline Miller: “The ships were golden and huge as leviathans, their rails carved from ivory and horn. They were towed by grinning dolphins or else crewed by fifty black-haired nereids, faces silver as moonlight.”

Related term: metaphor

Authors turn to tangible symbols to represent abstract concepts and ideas in their stories Symbols typically derive from objects or non-humans — for instance, a dove might represent peace, or a raven might represent death.

Example: In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald uses the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg (actually a faded optometrist's billboard) to represent God and his judgment of the Jazz Age.

Related term: motif

Exercise: Choose an object that you want to represent something — like an idea or concept. Now, write a poem or short story centered around that symbol.

Synecdoche is the usage of a part to represent the whole. That is, rather than an object or title that’s merely associated with the larger concept (as in metonymy), synecdoche must actually be attached in some way: either to the name, or to the larger whole itself.

Examples: “Stanford won the game” (Stanford referring to the full title of the Stanford football team) or “Nice wheels you got there” (wheels referring to the entire car)

Related term: metonymy

Zeugma is when one word is used to ascribe two separate meanings to two other words. This literary device is great for adding humor and figurative flair as it tends to surprise the reader. And it’s just a fun type of wordplay.

Example: “Yet time and her aunt moved slowly — and her patience and her ideas were nearly worn out before the tete-a-tete was over.” — Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Zoomorphism is when you take animal traits and assign them to anything that’s not an animal. It’s the opposite of anthropomorphism and personification, and can be either a physical manifestation, such as a god appearing as an animal, or a comparison, like calling someone a busy bee.

Example: When vampires turn into bats, their bat form is an instance of zoomorphism.

Exercise: Describe a human or object by using traits that are usually associated with animals.

Related terms: anthropomorphism, personification

French for “straddle,” enjambment denotes the continuation of a sentence from one poetic line to the next. It’s the opposite of an end-stopped line.

Example: The first line in T.S. Eilot’s “The Waste Land” is an example of enjambment:

“April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing.”

Related terms: end-stop

Euphony is the acoustic effect of a combination of words that’s pleasing to the ear. Indeed, it leads by example: if you say “euphony” out loud, the assonance of the word itself is harmonious.

Example: “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? / Thou art more lovely and more temperate.”

Related terms: cacophony, alliteration

63. Pathetic fallacy

Pathetic fallacy is a form of personification, where an author gives human emotions to an inanimate object.

Example: “The sky wept.”

If you like puzzles, you might have already heard of an anagram: a new word or phrase a writer can form by re-ordering the letters of another word. Note that an anagram is not the same as a palindrome or a semordnilap, as the letters need to come in a different order, and not simply read back to front.

Example: “brag” is an anagram of “grab,” and vice versa. We can go on. “Night” is an anagram of “thing”!

Related terms: palindrome, semordnilap

Made up of two different words (“anti” and “thesis”), antithesis is a literary device that juxtaposes opposing ideas, words, or images. Usually, these two contrasting ideas will be written with similar grammatical structure for dramatic effect.

Example: Neil Armstrong perhaps unintentionally created an example of antithesis when he famously said, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Related terms: juxtaposition

Circumlocution is the opposite of saying something directly: instead, it’s when a writer states something in an ambiguous, unclear, or roundabout way. “Talking in circles” is the end result.

Example: Look to any politicians for examples of circumlocution. The pigs in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, for instance, vaguely say in many words, “For the time being it has been found necessary to make a readjustment of rations,” in order to mask the fact that they’ve simply stolen food from the other animals.

Related terms: periphrasis

In literature, an epigraph is the quotation (or sometimes the phrase) at the beginning of a book or chapter. It’s entirely optional on the author’s part, but can offer a thematic direction for the reader.

Example: In The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway uses Gertrude Stein’s “You are all a lost generation” quote to kick off a chapter.

Related terms: intertextuality

Mood in writing refers to the emotions that the writer makes a reader feel through the text. Many factors contribute to this effect, but the writer’s use of language is perhaps the most primary of them.

Example: When you read an Agatha Christie novel, what do you feel? Happy? Excited? Joyous? Probably not. You’re more likely to be nervous, anxious, and tense because of her stories — and that’s in part due to the suspenseful mood she successfully creates through her language.

Related terms: atmosphere

Diction refers to the words that an author chooses to put in writing. This linguistic choice helps the writer express an idea, or achieve a certain effect. In speech, it also refers to the style of enunciation.

Example: The diction that an author chooses for their characters is important, and can tell you about the characters themselves — whether they’re rich or poor, where they’re from, and how old they are. “

Related terms: tone, dialogue, narrative voice

As a literary device, a vignette is a short scene without a beginning, middle, or end. Instead, it starts in medias res and captures a certain moment in time or is a character-creating detail.

Example: The cold opens of many sitcoms are great examples of vignettes. They are short scenes unrelated to the main plot of the episode, but set the humorous mood that will follow.

Related terms: in medias res

A foil character is a supporting character whose main purpose is to provide contrast to the protagonist in some shape or form, whether it’s the protagonist’s traits, dreams, or goals.

Example: In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Wickham serves as Mr. Darcy’s foil. Without Wickham’s decadent, gold-digging ways, we’d never learn the extent of Darcy’s honesty, or his goodness.

The term antistrophe describes a specific type of repetition — that of a word, or a phrase, repeating at the end of consecutive sentences. You’ll commonly see it used in poetry, although books and speeches will also make use of it.

Example: “Wherever there's a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. […] An’ when our folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build — why, I’ll be there.” — John Steinbeck, Grapes of Wrath

As you’re reading this post, do you find it readable? Congrats: you just encountered a case of polyptoton, which is otherwise known as the repetition of two words that share the shame root (“reading” and “readable,” for instance, “trick” and “trickery,” or “ignorant” and “ignorance.”)

Example: In the phrase, “Who shall watch the watchmen?”, the repetition of “watch” and “watchmen” is an example of polyptoton.

Anthimeria captures the act of turning a word from one part of speech into another: for instance, when an author uses a word that was originally a noun as a verb.

Example: “Chill” is perhaps a popular example by now. Originally a noun, it’s now used everywhere as a verb that means “to relax.”

A double entendre is exactly what it says on the tin: a word with two, or double, meanings. What’s more? Often the second meaning is something a tad risqué.

Example: William Shakespeare was a master when it came to double entendres. Just take Mercutio’s statement: “Ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man.” Here, the word “grave” pulls double duty, as it means both to be “serious” and hints at death.

Related terms: pun

Paraprosdokian literally means “against expectations” in Greek—so you might be able to guess how it functions as a literary device. Yep, that’s right: it describes a sentence with an unexpected ending.

Example: As Oscar Wilde once said, “Some cause happiness wherever they go. Others, whenever they go.”

Related terms: paradoxical

Whenever a text is referenced, either directly or indirectly, in another text, that’s an instance of intertextuality: the derived relationship between two works.

Example: Every reference that the musical “Hamilton” makes to another musical is an example of intertextuality.

A palindrome is the easiest literary device on your eyes: it’s a word or phrase that you can read the same either backward or forward.

Example: “Madam, I’m Adam” is exactly the same read backward as it is read forward. “Radar,” meanwhile, is an example of a word that’s a palindrome. Or the famous “Redrum” from The Shining.

If you’ve ever mispronounced a phrase before, you might’ve accidentally created a spoonerism, which refers to a person swapping the sound of two or more words.

Example: You’d be committing a spoonerism if, instead of “bunny rabbit,” you said “runny babbit.”

As a narrative device, an ellipsis means the omission of certain words or parts of the plot, so as to give the readers an opportunity to fill in the gaps themselves.

Example: In The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald lets the ellipsis form a time lapse that is up to the reader to interpret: “ . I was standing beside his bed and he was sitting up between the sheets, clad in his underwear, with a great portfolio in his hands.”

Literally, a parataxi describes the placing of consecutive words without a connecting word to show the relationship between them. It is different from hypotaxi, as you’ll soon see.

Example: “I came, I saw, I conquered.” — Julius Caesar.

Related terms: hypotaxi

A hypotaxi is the opposite of a parataxi in that it adds connecting words (or conjunctions) to show readers exactly what the relationship between two clauses is.

Example: In the sentence, “I ate an apple because I was hungry,” the word ‘because’ makes it a hypotaxi.

Related terms: parataxi

Aporia captures the moment when the speaker pretends not to know something, or expresses doubt, in order to prove a point. Often this confusion is completely feigned when used rhetorically, bordering on irony, although sometimes it can be genuine.

Example: As Elizabeth Barrett Browning once asked, “How do I love thee?”. Or, like when someone replies “I don’t know, can you?” when you ask if you can use the bathroom.

Related terms: irony

We’ve covered polysyndetons. Now get ready for its sibling, the asyndeton, which describes the act of intentionally omitting conjunctions in a sentence.

Example: “Live, laugh, love.”

Related terms: polysyndeton, syndeton, parataxi

Nope, this isn’t the kind of meiosis you learned about in high school biology! In literature, meiosis is instead a rhetorical device where the speaker understates something to belittle a undermine or situation.

Example: You’d be using meiosis if you said “Oh, it’s only a scratch” to describe a deep, gaping wound that’s bleeding out of the bone.

A paralipsis is what it’s called when you emphasize something about a situation, person, or topic by claiming that you don’t know much about it. Yes, it’s a little passive-aggressive, if that’s what you’re also thinking right now.

Example: “Of course, that’s not to mention my most hated enemy’s billion-dollar debt, nor their complete unwillingness to pay it.”

Related terms: apophasis

An overstatement is the best literary device of all time. There’s nothing better in the world than an overstatement (which is when you exaggerate your language to make your point in some shape or form).

Example: “This is officially the worst day of my life,” one says, upon accidentally dropping one’s ice cream cone on the ground with a splat.

Related terms: understatement

As another rhetorical device that’s just slightly passive-aggressive, an apophasis does the trick of bringing up a subject by denying that you’re bringing it up.

Example: “We won’t speak of his absolute inability to be a decent human being. Nor will we even begin to speak of his atrocious gambling problem.”

The opposite of euphony, cacophony is the term used to describe a combination of discordant tones that do not sound good together.

Example: You’ll see this literary device used a lot in poetry, for instance, in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”:

"With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

Agape they heard me call:

Related terms: euphony

Connotation refers to what an author or speaker implies through the use of a particular word. It’s usually non-literal, and up to the reader to interpret.

Example: The connotation of the word “miserly” is quite negative, and evokes the image of a Grinch hoarding money, while “frugal” connotes someone who’s merely thoughtful about saving money.

When you choose to use an offensive or derogatory term in place of a neutral or agreeable one, you’re using a dysphemism.

Example: “He’s a nerd” instead of positively describing that someone is smart or factually stating that someone often studies is an instance of a dysphemism.

Related terms: euphemism

Inverting the regular sequence of words is called a hyperbaton. Authors generally do this to call emphasis to a certain phrase, or part of the sentence.

Example: Yoda from Star Wars is a famous abuser of hyperbaton, with his Go you must’s and Miss them, do not’s.

Related terms: anastrophe

In literature, metanoia is a self-correction, or when a writer deliberately takes back a statement they just made in order to re-state it.

Example: In the Hippocratic Oath that doctors take before getting their credentials, they promise “To help, or, at least, to do no harm.” The second half of it is the instance of metanoia.

You know them. You love them. Yes, puns, or jokes that are wordplays on the different meanings or sounds of a word, are also literary devices that authors use to add humor to a piece of writing.

Example: “Denial isn’t just a river in Egypt.”

Parentheses are a form of punctuation, but when used in literature, they can insert information that authors would like to add for detail.

Example: Author Sarah Vowell once wrote in her book, Take the Cannoli, "I have a similar affection for the parenthesis (but I always take most of my parentheses out, so as not to call undue attention to the glaring fact that I cannot think in complete sentences, that I think only in short fragments or long, run-on thought relays that the literati call stream of consciousness but I still like to think of as disdain for the finality of the period)."

Like its psychological definition, synesthesia in literature describes the conflation of two senses. This might materialize in the author using one sense to describe another, or blend the two altogether.

Example: "The silence that dwells in the forest is not so black." — Oscar Wilde

Eutrepismus is a long word for a simple concept: stating your points in a numbered list, so as to structure your speech, or dialogue.

Example: “Firstly, you’ll want to read this post. Secondly, you’ll want to memorize every single literary device on it.”

Epizeuxis is another hard-to-spell-and-pronounce literary device that captures a very simple concept: it’s the repetition of a word to emphasize it.

Example: “Hark, hark! The Lark!” — William Shakespeare

Narrative voice is the voice from which a story in literature is told. It encompasses all of the decisions that an author makes in regards to voice, including tone, word choice, and diction.

Example: First-person books like Catcher in the Rye provide good examples of books written in a strong narrative voice.

We saved one of the most obscure (and best!) literary devices for last. Syllepsis is another form of wordplay (similar to a pun) where a word, usually a verb, is used in multiple ways.

Example: “She blew my nose, and then she blew my mind.” — The Rolling Stones

Related terms: zeugma, pun

Readers and writers alike can get a lot out of understanding literary devices and how they're used. Readers can use them to gain insight into the author’s intended meaning behind their work, while writers can use literary devices to better connect with readers. But whatever your motivation for learning them, you certainly won't be sorry you did! (Not least because you'll recognize the device I just used in that sentence 😉)

– Originally published on Mar 20, 2020

Ron B. Saunders says:

Paraprosdokians are also delightful literary devices for creating surprise or intrigue. They cause a reader to rethink a concept or traditional expectation. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paraprosdokian)

That's pore, not pour. Shame.

↪️ Coline Harmon replied:

It was a Malapropism

↪️ JC JC replied:

Yeah ManhattanMinx. It's a Malepropism!

↪️ jesus replied:

Susan McGrath says:

"But whatever your motivation for learning them, you certainly won't be sorry you did! (Not least because you'll recognize the device I just used in that sentence. 😏)" Litote

Comments are currently closed.

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

Character creation can be challenging. To help spark your creativity, here’s a list of 100+ character ideas, along with tips on how to come up with your own.

Introducing characters is an art, and these eight tips and examples will help you master it.

Want a handy list to help you bring your characters to life? Discover words that describe physical attributes, dispositions, and emotions.

Need to plot your novel? Follow these 7 steps from New York Times bestselling author Caroline Leavitt.

Want to write your autobiography but aren’t sure where to start? This step-by-step guide will take you from opening lines to publishing it for everyone to read.

The climax is perhaps a story's most crucial moment, but many writers struggle to stick the landing. Let's see what makes for a great story climax.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.