Gender equality and women empowerment have been on the top of the agenda globally. Achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls has been mentioned by the United Nations in its Sustainable Development Goal (SDG-5) as a target. Various efforts and initiatives have been taken at global, regional and local level to eliminate gender inequality. Women in India have been stereotyped and discriminated since ancient times due to the patriarchal mindset. Social evils such as sati, purdah system, female foeticide, female infanticide, dowry, domestic violence have been faced by women. Various constitutional and legal provisions have been framed to eliminate such evils. In contemporary times, women have become sensitised about their rights and have come a long way in terms of women empowerment. Various schemes have been launched by central and state governments for emancipation of women. However, the patriarchal mindset still exists and gender biasness is still experienced by women both in public and private space. The paper attempts to analyse the level of women empowerment in different states of India. The study is based on the secondary data collected from various government sources. An analysis of the reasons responsible for the trends has also been done. It has been found in the study that female literacy has a positive bearing on the health and decision-making of females. Also, government support in the from of infrastructure and schemes act as a catalyst in women empowerment. Women-centric organisations and Self Help organisations have promoted economic empowerment and decision-making of females.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Women empowerment and gender equality has become the pivot of all global agendas. The struggle for ending gender inequality and achieving emancipation of women is long drawn. Moreover, women empowerment is considered as a pre-requisite for the attainment of sustainable development (UNFPA, 2021). Gender equality and empowering women are not only an end in themselves but also a means to achieve a prosperous, peaceful, sustainable and inclusive world. United Nations have organized four conferences on women’s issues. The 4th conference popularly known as The Beijing Platform for action is a landmark event as it focuses on twelve critical areas of women’s concern and imagines a world where each woman and girl can exercise her freedom of choices (UN Women, 2014). The sustainable development goal mentions achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls as a specific objective to be achieved by 2030. (Women and Health, 2021). Several conventions such as Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against women, Convention on Political Rights of women, Declaration on the Elimination of violence against women have been adopted to end gender discrimination (International conventions on women, 2020).

Though numerous efforts have been initiated for providing a discrimination free world to women but the statistics throughout the world still paints a gloomy picture. According to UNDESA, one in three women (736 million) have been subjected to physical and or sexual violence at least once in their lifetime, since the age of 15. Also, according to a statistic, only 28% of women held managerial positions throughout the world. Moreover, it was also pointed out that the burden of unpaid domestic care and work is lopsided which further increased during the pandemic (UNDESA, 2020).) According to Global Gender Gap Report, the COVID 19 pandemic has increased the time period for gender parity to be achieved from 99.5 years to 135.6 years (World Economic Forum, 2021).

Indian constitution treats its women at par with men through various constitutional (Article 14, 15, 42) and legal provisions (Planning Department, 2021). Moreover, it provides for affirmative action in favour of women to end the age-old discrimination and provide equal opportunities. 73rd and 74th constitutional Amendments provide reservation to women in local bodies so as to make them politically empowered and have a say in decision- making (Hazarika, 2011). Numerous women targeted schemes have been launched since Indian Independence such as Pradhan Mantri Janani Suraksha Yojana, Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, Ujjawala. SwadharGreh, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana etc. (MOW & CD, 2021). However, even after more than seven decades of independence and numerous initiatives, the Indian women face lot of discrimination and injustice. The longstanding and intergenerational cycles of gender biasness impacts both the present as well as the future of the country. (Pradhan, 2020). According to recent report released by World Economic Forum, India has slipped 28 places and ranked 140th among 150 nations in global gender gap. The gap in India has widened to 62.5% due to various factors such as decrease in women’s labour force participation, inadequate representation of women in politics and leadership roles, lagging female to male literacy rates (Shettigar & Mishra, 2021). The major hindrance in achieving gender equality lies in the implementation of laws and schemes coupled by the gendered vision of patriarchy (Saxena, 2019).

The present paper attempts to examine the educational, health, economic, political and socio-cultural status of women in different states of India. The papers also aim to analyse the overall level of women empowerment achieved by the states. Moreover, the papers also attempt to scrutinize the reasons responsible for the emerging trends in different states.

The concept of empowerment is multi-dimensional in nature. One of the models stresses that empowerment is based on three interrelated elements known as resources (material, human and social), agency (ability to define one’s goal and act upon them), and achievements (outcomes) (Kabeer, 1999). Kabeer’s model focused on individual aspects and identified four core concepts of empowerment that is assets, knowledge, will and capacity (Singh & Singh, 2020).Women empowerment has often been defined as allowing and equipping women to make life choices so that they can become self- reliant and have a sense of self-worth (Bayeh, 2016; Kaviarasu & Xavier, 2006; Mallik, 2021, Krishna, 2016).Women empowerment and autonomy is very important in itself and also for achieving sustainable development (Sen, 1999; UNFPA, 2021; Loya, 2021; Farzana et al., 2018).Promoting gender equality and empowering women can positively affect child nutrition, growth and reduce domestic violence (Sethuraman, 2008). Various approaches have been developed for empowering women. The welfare approach was the earliest approach which sees women as passive recipients rather than active participants in the process of development. It addresses women’s reproductive role and focuses on welfare schemes for improvement of women’s life. Another approach known as women in development challenged the welfare approach. It gives importance to women’s productive role and their integration into economy as a way to improve women’s status. According to this approach there is a symbiotic relationship between economic development and women empowerment (Duflo, 2012). Later on, an approach known as Gender and Development (GAD) was developed which identifies the social and cultural constructs and refers to the relative position of men and women within family as well as society. It emphasizes that both women and men should participate in development and should equally benefit from it. It focuses on transformation via top- down intervention. A more recent approach called as empowerment approach is gender sensitive in nature and highlights women’s subordination in different spheres of life. This approach is grassroot oriented and gives importance to bottom -up intervention. Its aim is to increase the self-reliance of women and influence change in various aspects such as policy, legislative, societal. A great stress is given to women’s autonomy in decision -making as they are treated as active participants rather than passive recipients. (Collins, 2013; Muyoyeta, 2007; Siddgowda, 2015; Shunmuga et al., 2015; Tasli, 2007; Valimaa, 2004).

Numerous measures have been formulated to understand the level of women’s empowerment at international and regional levels. Until 1990s, the measurements used to assess the progress in a country were GNP, GDP and per capita income which were more economy oriented. Gender Development index (GDI) by UNDP adjusts human development index for gender inequality. The three indicators are health, Knowledge and GDP relating to purchasing power of a country. Another measure Gender Empowerment Index (GEI) measures gender inequality in key areas of economic and political participation and decision- making. It differs from GDI as GEI focusses on decision making while GDI works on basic indicators (Muyoyeta, 2007). World Economic Forum releases Gender Gap Index which includes a broad range of dimensions such as economic participation and opportunity, political empowerment, educational attainment, health and well- being (Lopez-Claros and Zahidi, 2005; Asalu et al., 2018). Regional indicators have also been developed which adapt to GDI and GEM. African Gender Development Index (AGDI) includes social, economic and political parameters. Social indicator includes education and health, economic indicator includes income, employment and access to resources. Political parameter includes representation in key decision- making positions in public sector and civil society respectively (UNECA, 2009). Thus, it can be said that measurementof women empowerment includes a broad range of parameters that is education, health, economic participation, socio-cultural and political opportunity (Chang, et al., 2013; Sharma & Sanchita, 2017).

India accounts for 2.4% of world’s total land area and about 17.7% of global population as per UN Population Division (Kumar, 2021). According to World Bank, out of total Indian population, 48% are females (Trading Economics, 2022). The population of India has successively increased through decades except during 1911–1921 (Hussain, 2014). Urban population is also increasing and recorded a rise between 1950 and 2015 from 17.1 to 29.2% (Gulankar, 2019). The overall literacy rate of India as estimated by census 2011 was 74.04, 82.14 for males and 65.46% for females (India Book, 2020). The sex ratio of India increased from 933 females per thousand males in 2001 to 940 females in 2011. The total fertility rate has noticed a declining trend from 2.7 in 2005–06 to 2.1 in 2019–20 (Arora, 2021).

The Indian Constitution’s Preamble, Fundamental Rights, Fundamental Duties and Directive Principles all explicitly state the importance of gender equality. In addition to guaranteeing women’s equality, the Constitution gives the state authority to implement measures that positively favour women (National Legal research Desk, 2012). Various constitutional provisions like Article 14, 15, 15 (3), 16, 39 (b), 39 (c) & 42 were formulated for empowering women. Article 243 provides for reservation of women in local bodies. Women’s rights have evolved overtime to provide an egalitarian setting.

To further guarantee women’s rights, India has ratified a number of international conventions and human rights treaties. The ratification of CEDAW (the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women) in 1993 is a major step in the right direction. The National Commission for Women was established in 1990 after legislation was passed to safeguard women’s rights and legal standing. Equally important, 2001 was designated by the Indian government as the “Year of Women’s Empowerment”. In 2001, legislators also established the National Policy for the Advancement of Women.

The study is based on the data collected from different secondary sources. These secondary sources are as follows:

Selection of Indicators: Five types of Indicators are selected for the creation of Women Empowerment Index (Bansal, 2017). Different kinds of sub indicators are combined to form these selected indicators. The following Table 1 illustrates the different indicators that are chosen in our study.

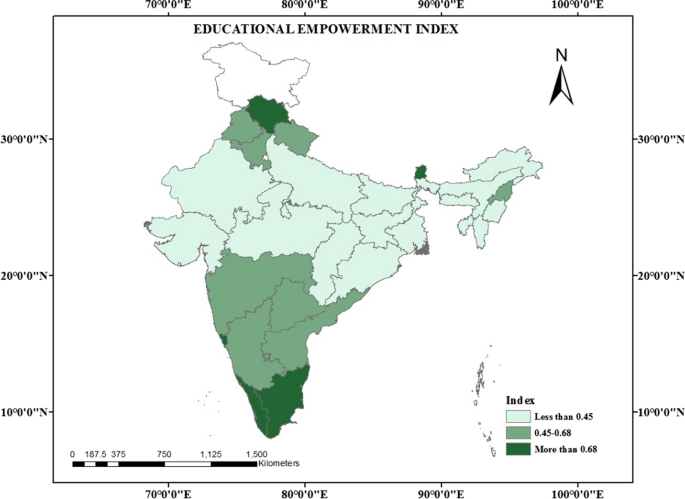

According to the results, Jharkhand and Biharrank lowest in the educational index with a value of 0.22 and 0.23 respectively. This implies that the condition of female education in this state is quite pathetic. Out of 4 indicators on education, Bihar and Jharkhand lies in low category in 3 indicators. According to NFHS-5 data the women literacy rate in Bihar is 55% and there are only 28.8% females who have attended school for 10 or more years. The Female Gross Enrolment ratio in Higher education is also quite poor with only 13.1% females attending higher educational institutes. The dropout rate of girls at primary level is 1.5. Literacy rates and learning outcomes are lowest in the BIMARU (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) states (Balani, 2017). This is also found in our results where these states perform quite poorly in educational index having a value below 0.45. Rajasthan has high literacy gender gap. According to PLFS data (2017–18), one out of every two female is illiterate in Rajasthan (). Some of the reasons which act as hindrance in female education especially in rural areas are poor school environment for girls which lacks separate washrooms, inadequate number of female teachers, low female enrolment or high dropouts due to family responsibilities, dowry system, early marriage, priority to son’s education over daughter, poverty and gendered vision of patriarchy which views females as care-givers and males as the breadwinners of the family (Azad India Foundation, 2020; Choudhary, 2019; Mishra, 2019).

Some of the best performers in the educational component are Kerala, Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh, Goa and Tamil Nadu have an index value above 0.68. Kerala ranks number with an index value of 0.89. The state performs quite well in all the four indicators taken under educational component. It has the highest female literacy rate (97.4%) and 77% of females have attended school for 10 or more years, according to the NFHS 5 data. According to a study by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Kerala records highest age specific attendance ratio for women from pre- primary to pre- university education (Abhinandan, 2020). Himachal Pradesh and Tamil Nadu also perform quite well in age specific attendance ratio of women (Chandra, 2019a, 2019b). Himachal Pradesh and Sikkim government is giving priority to education sector especially female education and investing in educational infrastructure (Rana & Jyoti, 2018).

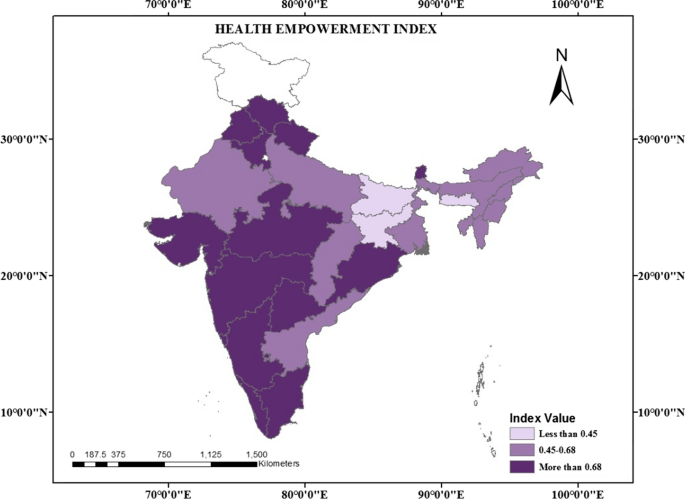

Women’s health is another crucial parameter for measuring women empowerment and it has been used in various indices for calculating the status of women. Women’s health concerns are complex unlike men,as they are influenced by multifarious factors such as biological, cultural and social (Kalra, 2019; Singh, 2020; Tinker et al., 2000; WHO, 2021; Women & Health, 2021) (Fig. 2).

The study uses 5 indicators to study the health component of females. It includes three positive parameters that are Current use of family planning methods by females (15–49 years), institutional births, mothers or pregnant women who consumed iron folic acid for 180 or more days. Two negative parameters such as Total Fertility Rate and Adolescent Fertility Rate have been included. Overall, three states that is Meghalaya, Bihar and Jharkhand falls in low category having an index value below0.45. Meghalaya ranks last with an index value of 0.22. All the three states falling in low category have a high Total fertility rate (TFR) that is above 2 (Pathak, 2021). Bihar’s TFR has declined from the previous 3.4during NFHS 4 (2015–16) to 3 during NFHS 5 (2019–21), but still, it is the highest among all states in India. Moreover, Bihar and Jharkhand have high adolescent fertility of 77 and 64 respectively. Early marriages coupled with long reproductive period and high TFR leads to complication during and post pregnancy causing high Maternal Mortality Rate (Kumari & Verma, 2021). Some of the reasons responsible for such precarious condition of women’s health in these states are institutional factors that is poor health infrastructure, lack of specialist doctors, inadequate obstetric care and social factors including gender discrimination, poor education, low asset holding etc. (Kumari & Verma, 2021; Prakash, 2019). Many tribal regions of Jharkhand record miserable condition of women due to existing superstitions, ignorance regarding immunisation and vaccination, poor personal hygiene leading to reproductive health problems (Ghosh, 2017).According to Jharkhand Economic Survey 2015–16, more than 90% of expectant mothers in rural areas are unaware of adequate health and nutrition requirements (Choudhury, 2016).

Goa ranks first in the health component having an index value of 0.91, followed by Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Sikkim. All these states perform quite well in all the indicators mentioned under this component. All these states record more than 90 per cent of institutional births and low Total Fertility rate (TFR). Sikkim has the lowest TFR of 1.1 followed by Goa (1.3), Kerala (1.8) and Tamil Nadu (1.8). Goa and Kerala records some of the lowest Adolescent Fertility rates of 14 and 18 respectively. Teenage childbearing leads to heightened risks for mothers and their infants, low educational attainment and inadequate economic participation (Dehury & Mohapatra, 2019; Klepinger et al., 1999; UNDESA, 2013). Good performance in per- capita income, extensive healthcare systems, high female literacy rate, affordable, accessible and good quality of services in public health and greater sensitization are some of the major determinants of high female health index in Kerala and Goa (Dehury, et al., 2017; Jose et al, 2014; Singhal & Andrade, 2013).

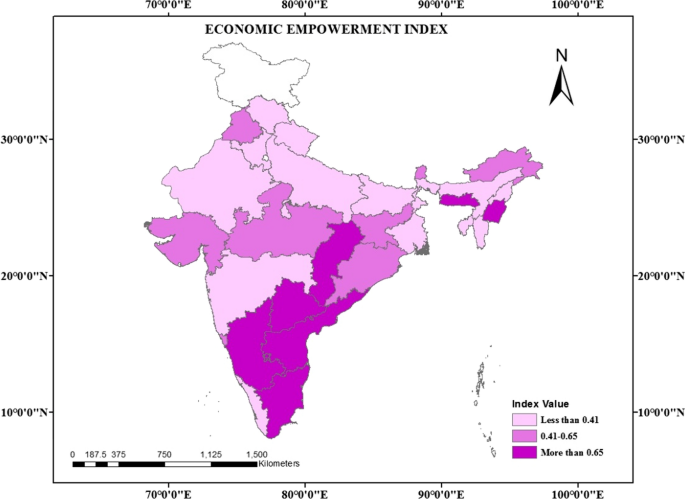

Economic empowerment of women is a transformative process by which women and girls go from limited choices at home and economy to having the skills, resources and opportunities acting as a catalyst not only for economic development but also adding a sense of self-worth (Ayene, 2016; Kishor & Gupta, 2004) (Fig. 3). Economic emancipation of women also has social benefits as women spend more on their families, boost demand, have healthier and better educated children improving the human development levels (UN India n.d.)

According to the result, states having low female economic empowerment are Nagaland, Tripura, West Bengal and Uttarakhand. Nagaland has worst performance in all the three indicators included in economic component. Only 26.9% of women own a house and or land (alone or jointly with others), just 23.6% women have worked in last 12 months who were paid in cash and a low of 63.7% women have a bank or savings account which they use themselves. Tripura has the lowest percentage of women owning a house or land(alone or jointly).Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and West Bengal have below 25% of women who worked in last 12 months and were paid in cash. Some of the systemic constraints recognized by UN having negative impact on economic empowerment of women are adverse social norms, discriminatory laws and lack of adequate legal protection, non- recognition of unpaid work and lack of access to property, financial and digital assets (UN secretary General, 2016).

Seven states fall in the high index category having a value above 0.65. Out of these seven states, four are from South India which are comparatively better in socio-economic terms than their counterparts. Telangana is on top with an index value of 0.89 followed by Karnataka and Tamil Nadu with index value 0f 0.86 and 0.82 respectively. Women in Telangana performs very well in all the three indicators with about 66.6% women owing a house and or land. Telangana has nearly 4 lakh Self Help Groups with nearly 43.4 lakh members, which is quite significant for economic and social upliftment of women belonging to low- income groups and underprivileged sections (Telangana Socio- Economic Outlook, 2021). Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu scores exceptionally well in terms of women having a bank or saving account used by themselves. According to a report by MOS & PI, Telangana has highest percentage of working women in India including the organized sector (Nilesh, 2020). North–Eastern states like Manipur and Meghalaya also fall in the high category. Meghalaya has a matrilineal society where women enjoy property rights and have more autonomy than their counterparts. In most tribal societies economic participation of women is an important feature (Meghalaya Development Report, 2008).

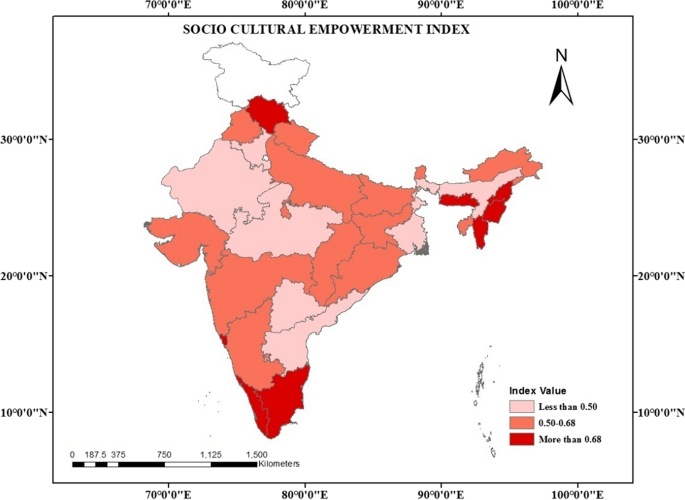

The socio-cultural parameter is vital for women empowerment. Indicators like crime against women, child marriage, sex ratio and decision making of women are important for determining the status of women. Gender stereotypes and prejudice are often embedded in social and cultural factors (Fig. 4).

The states which perform quite horribly in this parameter are Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and West Bengal. According to UNICEF, over half of Indian child brides live in five states that is Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh. Child marriage is a violation of human rights which needs to be eliminated as targeted by SDG 5.3 (UNICEF, 2019). Some of the determinants of child marriage are poor education and literacy of women, economic status of family, region of domicile, place of residence (urban/rural), religion and caste (Child Rights and You CRY, 2020). The states still having low sex ratio include Gujarat, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh and Punjab. Haryana and Punjab have worst sex ratios of 926 and 938, respectively. Strong son preference and practices like female feticide and infanticide are quite dominant in these states. Another determinant which significantly affects women’s daily lives are crime against women. According to the data by NCRB Assam records highest crime rate of 154.3 which is almost three times the national average of 56.5 (Ramesh, 2021). For the fourth consecutive year, Assam remains on the top with marked increase in cases of domestic violence, kidnapping and molestation cases of women. According to NFHS 5 data, over 30% of women reported spousal violence and 8% recorded sexual violence (Chathopadhyay, 2021). Other states where rate of crime against women is quite high are Odisha, Rajasthan, Telangana and Haryana. Some of the factors pointed out for such a horrifying scenario is poor conviction rate and existing patriarchal mindset (Saini et al., 2021). However, it is also pointed out that the increase in numbers is due to increased reporting of crimes which is a silver lining (Ramesh, 2021).

The states following in high category are dominated by North- Eastern states like Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland. Nagaland ranks at top with an index value of 0.86. It records lowest crime rate against women and a meagre 5.6% of child marriages. Also, it shows good performance in terms of sex ratio (1007 females per 1000 males) and female decision making (99%). Participation rate of women in decision––making at household level related to their own healthcare, making daily purchases and visits to family/relatives’ is quite high among North–Eastern states as compared to other regions (Banerjee, 2015). The women belonging to North–Eastern region, especially tribal women tend to have more autonomy in terms of decision- making at household level and enjoy better status due to absence of various social evils such as dowry, female infanticide, honour-killing etc. (Buongpui, 2013; Khonglah, 2008). According to the recent NFHS 5 data, India has made a marked improvement in terms of Sex Ratio where there are 1020 women for every 1000 men. However, it has also been pointed out that this statistic might be flawed as NFHS counts certain women belonging to specific demographic categories (Mishra, 2021). Himachal Pradesh and Kerala also perform quite well in terms of sex ratio and female participation in decision–making at household level. Both these states have a smaller number ofincidences of women marrying before the age of 18 years.

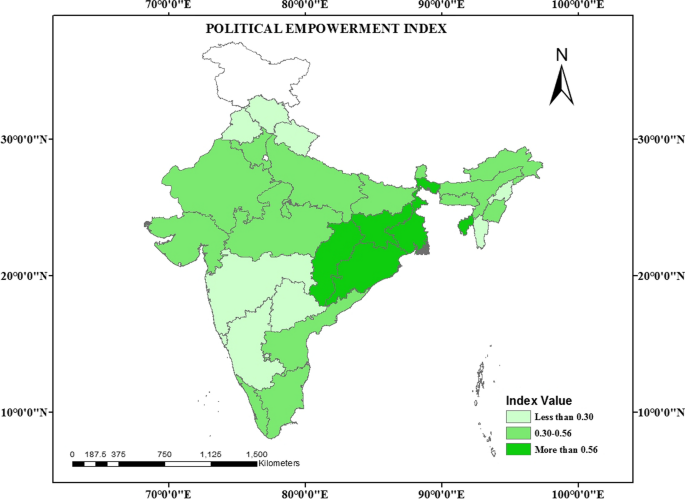

Political representation and participation have been recognised as important parameter for women empowerment in various indices (Fig. 5). Women’s participation in decision- making at higher levels is crucial for women’s interests and issues to be adhered to. Moreover, it helps in creating a gender-sensitive and an inclusive society (Devi & Lakshmi, 2005; Nisha & Vezhaventhan, 2018).

Overall, participation and representation of females has been in Indian politics is quite low. The recent 19th Lok Sabha elections recorded the highest number of women elected candidates in India history. However, they just constitute 14.3% of the total parliamentarians. Looking at the statistics, this component presents a very different scenario as most of the states with best socio-economic indicators have poor performance in this component. The states falling in high category are Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Tripura and West Bengal which do not fare very well in other women empowerment indicators. Tripura ranks at the top having an index value of 0.91. The state has recorded very high female voter turnout in the 17th Lok Sabha. The state has 50% representation in terms of female candidate elected and candidate contesting the election. However, there is a need to notice that the allocation of seats in Lok Sabha is on the basis of population. As a result, 2 seats have been allocated to Tripura, out of which on one seat female candidate has been elected. The maximum number of seats that is 11, has been bagged by women in Lok Sabha belongs to Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal followed by Maharashtra and Odisha (Suresh, 2019).

The states falling in the low category in this index are Uttarakhand, Telangana, Punjab, Nagaland, Mizoram, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Himachal Pradesh and Goa. States like Maharashtra, Mizoram and Punjab record some of the lowest female turnout in the 17th Lok Sabha. Goa and some north- eastern states like Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland have no female representation in the Lok Sabha. One of the reasons for such a scenario is number of seats allocated to these states. Mizoram and Nagaland have only one seat in Lok Sabha. Goa and Himachal Pradesh have two and four seats respectively.

There is a need to understand that irrespective of the performance of individual state in this component, the overall performance of India is quite dissatisfactory as women are considered incapable of taking up leadership roles. Moreover, patriarchal mindset still exists and female candidates often face derogatory comments and trolling on social media. Another aspect of female representation in Indian politics is the existence of proxy candidates where women candidates who get elected due to reservation are mere puppets in the hands of male guardians (Nisha & Vezhaventhan, 2018; Venkiteswaran, 2021).

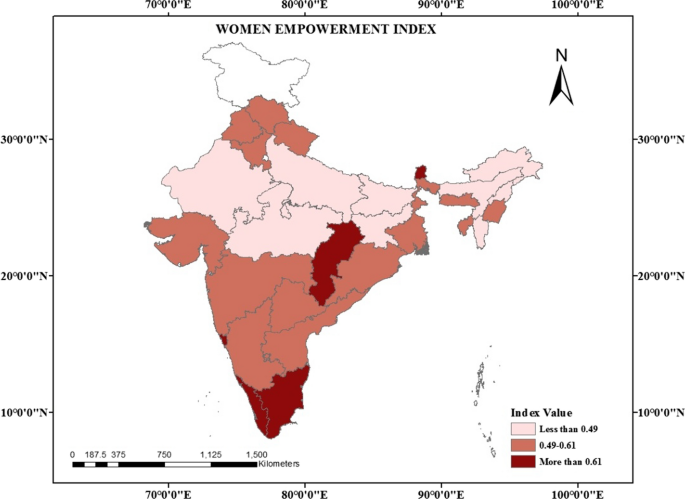

Tamil Nadu ranks first in women empowerment index with a value of 0.71. Out of the five indicators used in calculating the index, Tamil Nadu falls in high category in four of them. Tamil Nadu has one of the highest female literacy rates of 84% and a dropout rate at primary level of 0.8% (Fig. 6). Tamil Nadu government has launched various schemes for women education such as Periyar EVR Nagammar for female students for all communities to reduce the female dropout rate (Gokila, 2015). In the health component also, it falls in high category with having almost universal institutional births and a low fertility rate of 1.8. Moreover, about 92% women have a savings or bank account which they use themselves. Self Help Groups have been quite successful in Tamil Nadu leading to socio-economic empowerment of rural women promoting saving habits, nurturing entrepreneurial skills and participatory approach (Premaand Veeramuthu, 2019). One of the most recognised SHG in Tamil Nadu is Mahalir Thittam which acted as a catalyst in promoting gender equality (Seenivam, 2012). The sex ratio in the region is quite impressive as there are 1088 females for every 1000 males and more than 90% females participate in decision- making at household level. Tamil Nadu has one of the lowest incidences of crime against women. In the political component, Tamil Nadu falls in the medium category where the state recorded 72% female voter turnout during the 17th Lok Sabha but has very minimal female representation in the Lok Sabha. Kerala ranks number two having an index value of 0.67. It falls in high category in health, education and socio- cultural components. However, it has mediocre performance in terms of female political representation and a very poor performance in economic participation. In the education component, Kerala ranks at top with highest female literacy rate in India and zero dropout rates at primary level. The state also fares well in terms of socio-cultural components recording a very high sex ratio of 1,121 females per thousand males and about 94% females participating in decision- making at household level. It records very few cases of women marrying below 18 years of age and a low adolescent fertility rate. Kerala also exhibits good performance in terms of health component with almost universal institutional birth rate and a low total fertility rate of 1.8. It has been observed that regions having better female educational attainment and socio- cultural parameters have better female health. Education empowers women leading to delay in marriage age, reducing the chances of teenage childbearing, reduced total fertility rate thus improving the reproductive health of females (Bhupen, 2014) Kudumbashree, a women- centric organisation was launched by Kerala government with an agenda of poverty eradication and strengthening women community dealing with gender issues like women safety, domestic violence and financial empowerment (Kumar, 2018). However, Kerala performs poorly in terms of economic components where only 27% females own a house and or land (alone or jointly with others) and a meagre of 25% females who have worked in last twelve months were paid in cash. According to a study there exist a U–shaped relationship between the female labour force participation rate and education. (Shekhar, 2021). Absence of good quality formal jobs, increased expectation of educated females about jobs and rise in household income are some of the reasons which contribute to unemployment among educated females (Shekhar, 2021; Singariya & Shekhawat, 2015).Kerala falls in medium category in terms of political participation with 79% female voter turnout and only1 percent of female elected in 17th Lok Sabha elections. Thus, a kind of paradoxical situation exist in Kerala where on one high hand it records high achievements in terms of female health, education and socio- cultural components and on the other hand has a poor performance in political representation and economic participation (Selvi & Pushpa, 2017).

Goa ranks at number three with an index value of 0.65, followed by Sikkim and Chhattisgarh having an index value of 0.64 and 0. 61,respectively. Goa performs exceptionally well in socio- cultural, educational and health components, mediocre in economic and poor in political component. Goa records one of the highest female literacies of 92% and dropout rate at primary level is a low of 0.2%. The state enjoys better status in terms of women empowerment than rest of the country and it is mainly attributed to the unique set of civil laws governing the people. Registration of marriage is mandatory in Goa ensuring security to married women (Desouza, 2004). About 93% of women in Goa participate in decision–making at household level. Moreover, it has only 5.4% of females marrying before the age of 18 years. A high educational level and good socio- cultural environment ensures an impressive status of female health. Goa also records almost universal institutional births and a low total fertility rate of 1.3. Sikkim also performs well in health component of women empowerment with about 94% institutional births and 1.1 total fertility rate. Both the states have a good record in terms of monitoring the maternal health services through the mother and Child Protection card (Dehury et al., 2017). In Sikkim, women are considered as an asset and the condition of women is better as instances of dowry related deaths and female infanticide have not been reported (Rai, 2019). The women of the state have a mediocre performance in term of economic participation as more than half of women own a house and or land (alone or jointly with others). Sikkimese government is also promoting rural livelihoods and generating employment by investing in ecotourism, organic farming etc. NGOs and women led organisations like Mantalya and Nayuma Women’s Cooperative Society have played a positive role in upliftment of women by providing employment and taking care of distressed women (Subha, 2014). Chhattisgarh performs exceptionally well in terms of political and economic component, a satisfactory performance in socio- cultural and health and a very poor performance in terms of educational component having an index value of 0.43. 80% women have bank or savings account that they themselves use and about 45% of women own assets alone or jointly with others.

The states having a very poor performance in the women empowerment indicators are Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Nagaland, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. The BIMARU states as mentioned by Ashish Bose implies hindi word “Bimar” meaning sick. The states included in this are Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh were poor in developmental, social and demographic parameters (Khanna & Patil, 2020). These states are poor in socio-economic indicators as well as have a great degree of gender inequality and poor women empowerment level. Bihar ranks last having an index value of 0.37. Bihar has a very disappointing performance in terms of female education, economy and health parameters. The state has about 40% women who married before the age of 18 years and as a consequence a high adolescent fertility rate of 77. Rest of the states like Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan follows the same trend as that of Bihar with poor female literacy rates and high incidence of women marrying before the age of 18 years. There exists a positive relationship between female education and female health as the level of education significantly affects the fertility rate through women’s capacity to give birth, number of desired children, children’s health and women’s knowledge and decision-making in terms of birth control (Kim, 2016). However, states like Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh have a better performance in terms of political participation and representation of women.

Another set of states having a very dismal performance are North–Eastern states like Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Mizoram and Nagaland. These states are often characterized by diversity of cultures, beliefs, customs, languages and an egalitarian set up for women (Agarwal & Raj, 2020). However, the women of these states suffer from poverty, poor health, domestic violence and armed conflicts. These states have a satisfactory level of female literacy rate however, the dropout rate at primary level is very high thus leading to low index value in educational component. All the states except Assam have a very good track record in terms of socio- cultural component as tribal societies are free from social evils like strong son preference leading to a favorable sex ratio for women. Mizoram and Nagaland have very meager cases of females marrying before 18 years of age. Assam is at the top in terms of rate of crime against women. All the states belonging to this category have a decent performance in health component as all of them have reached replacement levels in terms of total fertility rate. The major problem is that of use of family planning methods and rate of institutional births which are quite less than rest of the country. In north–eastern states there exist a gap between the knowledge and utilization of modern family planning methods; however, the rate of contraceptive prevalence is quite lower among the tribal women as they still prefer traditional methods (Mog, et al., 2020). Moreover, vast difference exists in the utilization pattern of maternal health care in rural and urban areas (Gogoi, 2014). These states also lag behind in the political representation of females in Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies. Though the female voter turnout has increased in last few decades but there still exist an absence of women at the higher echelons of decision- making (Krishnaswamy, 2020). States like Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram and Nagaland does not any female representation in the Lok Sabha whereas Assam records a meager representation of one female candidate. One of the reasons for such a trend is the allocation of seats in Lok Sabha which is based on the population of the state. As a result, Mizoram and Nagaland have only one seat in Lok Sabha. This picture becomes more worrying when it comes to female representation at the level of state legislative assemblies where Mizoram and Nagaland have no representation whereas Arunachal Pradesh and Assam has only four and eight women representatives respectively.

The study’s originality comes in its use of a wide variety of indicators and sub-indicators to conduct a statistical analysis of the status of women’s empowerment in various Indian states and then to visualise those results using geo-spatial methods. The statistical findings have also been analysed and grasped with the aid of a wide range of literatures. The study makes an effort to paint a comprehensive picture of women’s empowerment across states in the current context.

The findings of this study will be useful for other scholars and policymakers in understanding the situation of women in various states. Furthermore, there is a great deal of room for future research in this area, as many other factors that contribute to women’s empowerment were not included either due to lack of data or due to its unsuitability.